John Cullen Murphy wanted to be a baseball player when he was a child, but he also possessed a rare artistic talent. Studying under the supervision of artists like Norman Rockwell, Franklin Booth, George Bridgman, and Charles Chapman, helped Murphy develop into a professional comfortable in any medium. Cartoons as well as portraits and magazine illustration were all equally crafted with skill and precision taught to him by his many distinguished mentors. Never neglecting his interest in sports, he got the attention of Rockwell who saw him playing baseball one afternoon and asked the boy to pose for some magazine ads. After Rockwell had done a few illustrations, he soon discovered John's keen interest in art. With a lot of encouragement from Rockwell, Murphy received his formal art training from the Phoenix Art Institute, the Grand Central Art School, and the Art Student's League.

John Cullen Murphy wanted to be a baseball player when he was a child, but he also possessed a rare artistic talent. Studying under the supervision of artists like Norman Rockwell, Franklin Booth, George Bridgman, and Charles Chapman, helped Murphy develop into a professional comfortable in any medium. Cartoons as well as portraits and magazine illustration were all equally crafted with skill and precision taught to him by his many distinguished mentors. Never neglecting his interest in sports, he got the attention of Rockwell who saw him playing baseball one afternoon and asked the boy to pose for some magazine ads. After Rockwell had done a few illustrations, he soon discovered John's keen interest in art. With a lot of encouragement from Rockwell, Murphy received his formal art training from the Phoenix Art Institute, the Grand Central Art School, and the Art Student's League.

At seventeen, Murphy's first professional work was drawing boxing cartoons for Madison Square Garden's publicity department. While still in High School, sports magazines in Chicago published on average two of his cartoons a week. When later serving in W.W.II, he further pursued his art career drawing spot illustrations for the Chicago Tribune, as well as painting portraits of famous military personnel including General Douglas MacArthur, while still meeting deadlines for magazine covers and other illustration assignments.

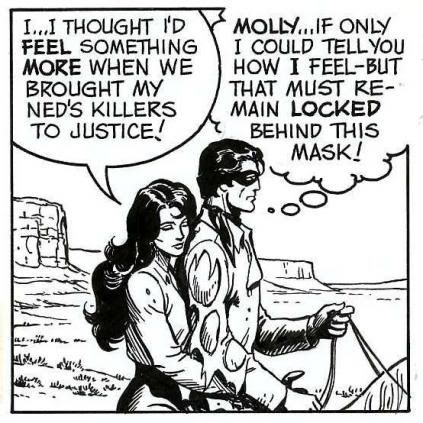

Upon his return from the Pacific, Murphy's watercolor boxing paintings in Collier's magazine got the attention of Elliot Caplin, who contacted the artist about collaborating on a boxing strip. The artist did two weeks of samples which Caplin quickly sold to King Features when William Randolph Hearst himself bought the feature. The two-fisted hero, Big Ben Bolt, debuted as a daily on February 20,1950 and a Sunday page followed on May 25, 1952. But Bolt was not your average sports character, a New Englander who graduated from Harvard, he was educated and refined, even in the brutalizing and corrupt world of professional boxing. The character had a kindness, integrity, and generosity that made the strip highly believable as well as entertaining. With his trusted fight manager, Spider Haines, Bolt would win the world's heavyweight crown, only to lose and regain it again as the strip progressed. With an eye injury in the mid-fifties, "Big Ben" became a sportscaster and journalist which lead him to new tales of adventure, mystery, and danger. Always a beautiful woman on his arm, he later dealt with topics concerning social reforms, conservation, and the troubled youth of America. Murphy's strong interest in sports and boxing background made the strip a real knockout with his fans. His vast experience as an illustrator and cinematic approach made any possible situation or local seem realistic and effective.

In 1970, Murphy was honored by Harold Foster's offer to take over the artistic chores on his signature strip, Prince Valiant, the saga of a young Norse prince who becomes a knight of King Arthur's round table at Camelot. It is viewed by many as the premier adventure strip of our time, with over half a century of classic stories and art. Murphy gladly took over the assignment while his assistants remained on Big Ben Bolt until its demise in 1978 with the death of the character. Murphy had approached Foster with samples two years earlier to inquire if he needed help on his strip. When Foster started to think about a possible replacement, three names came to mind, but Murphy's formal art training and illustration experience made him the perfect choice. From the fall of 1970 until early 1980 Foster would give a nicely penciled layout for Murphy to complete and be published.

When Murphy's oldest son, Cullen, graduated college in 1975 he used to contribute story ideas and outlines to Foster. His degree in medieval history persuaded Valiant's creator to use Cullen as the future writer of the Sunday. Bill Crouch also contributed six storylines over the next four years to the historic strip. After forty-three years of guiding his creation, Hal Foster retired from Prince Valiant, with his last pencil layout for February 10, 1980. Foster first debated ending his epic tale, but later reconsidered and sold the property to King Features recommending that John and Cullen continue the tales. Murphy's daughter, Meg Nash, also joined the family on the strip with her lettering and coloring of the Sunday page.

Murphy and his family worked on Val's adventures for thirty-four wonderful years before he handed over the feature to the current artistic team. The remarkable quality of this unique strip survived even thought the size of the page diminished greatly over the years. Murphy never tried to copy Foster's distinctive style. His preference for a harder pen line rather than a softer brush look helped give the strip a more angular feel than its original creator's version. Murphy was assisted by artist Frank Bolle in layouts and research, but John's detailed pen work could still be seen in all the finished pages. Murphy's superior illustrative skills was also highlighted by the expressions on the characters faces being confirmed in their hand placement and use in conveying the story. His enormous library of books and reference materials given by Foster, always made the episodes fresh with its many historical characters and places. With little known about the time frame of Prince Valiant, the fifth century after the fall of Rome, Murphy and his staff could take creative license to create a rich visual tapestry of castles and palaces with elaborate and ornate surroundings. John Cullen Murphy's talent and professionalism helped maintain Prince Valiant's worldwide popularity, and has won him numerous awards, including the National Cartoonist Society's Best Story Strip -- more than any other syndicated cartoonist. We are all fortunate that this young boy gave up his sports ambitions to become one of our most respected and thought of cartoonists in America.